Trading Places

| Site: | Helios Digital Learning |

| Course: | Trading Places: Understanding the Impact of Insider Trading (N. Smith) |

| Book: | Trading Places |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, January 8, 2026, 5:53 AM |

Description

TP

The story matters.(c)

(c) 2013 Helios Digital Learning. All rights reserved.

This e-case may not be duplicated, altered or distributed in any way without the express written consent of Helios Digital Learning, Inc.

Summary: If you anonymously asked the average employee their opinion on insider trading, what do you think their beliefs would be? This is a widely debated topic. Insider trading is defined as trading on nonpublic information. Although some people believe that insider trading is wrong because it gives certain individuals unfair market advantages, others believe that an “insider” has no moral obligation not to disclose a future price change to the public. Additionally, supporters of insider trading also believe that it does not create a loss, and therefore, no fraudulent action has been committed. However, according to the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission, insider trading is deemed illegal and carries heavy prison sentences.

This case explores the story of a day trader who was a member of a 17-year insider trading ring that resulted in profits in excess of $37 million. Despite the fact that his actions were illegal under U.S. law, more than 150 business school students wrote letters of support to the judge who presided over his federal prison sentencing hearing.

Learning Objectives:

After reading this case, students will be able to:

- Define insider trading.

- Gain an understanding of the ethical implications of insider trading.

- Gain an understanding of the history of insider trading.

- Improve critical thinking skills.

- Enhance writing communication skills.

Garrett Bauer was born on July 14, 1967 to a middle-class family and was raised in Long Island, New York. It was clear early on in Garrett’s childhood that he had a head for business. While most boys just delivered papers, Garrett did that and sold Christmas cards door-to-door. He was already going to the houses every day, so why not make a little extra money? As he grew older, Garrett juggled several jobs, including working at the local amusement park and at the ice-cream shop; he even tried his hand as a street vendor. Garrett was never intimidated by hard work and was always eager to make an extra dollar.

Garrett went on to study economics at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Upon graduation, Garrett moved to Manhattan and soon landed a job as a municipal bond administrator at the venture capital firm, Weiss, Peck & Greer. It was hardly a glamorous life, but it was a start.

By age 44, Garrett Bauer appeared to have it all. He was a successful day trader with millions in the bank and lived in a sprawling apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Garrett even bought his mother a house in Florida. He also regularly donated his time to helping others by volunteering at the Make-A-Wish Foundation, serving soup at local homeless shelters and working with autistic children; but Garrett’s perfect life was a facade.

It all changed on the morning of April 6th. As he was opening his eyes that morning, Garrett heard the distinctive sound of his elevator door opening and the familiar beep of his alarm system alerting him that someone had just entered the apartment. Garrett already knew who it was before he heard the shouts of “F.B.I.” drift into his bedroom.

The house of cards had fallen. For a number of years, Garrett had been part of one of the country’s longest insider trading schemes, and the F.B.I. had finally caught up with him.

Caption: Garrett Bauer describes his background.

Insider trading is defined as the buying or selling of company stock or securities for a profit based upon information that is not readily available to the public. A key distinction in this definition is the acquisition of “material nonpublic information.”

When a person engages in insider trading, it can be classified as a non-aligned employee workplace crime. With non-aligned employee crimes, the sole intention is for the individual to receive personal gain. These crimes are much more likely to be committed by employees at higher levels of the organization, such as managers and executives, because they have access to private company information and resources.

Material nonpublic Information is information that is material (i.e. important or of consequence) that is not publically available. This type of information is usually obtained by employees, managers, officers or other agents of an organization during the performance of their day-to-day duties. These people are known as insiders because they are inside the company.

For example, imagine you are an accountant at a company. Through performing the duties of your job, you learn that one of your clients exceeded their profit expectations over the previous quarter before the client announced that information to the public. This information would qualify as nonpublic information. As an agent of the company, you have a fiduciary duty, or legal obligation, to act in the best interest of the company and the clients your company represents. This includes keeping material nonpublic information inside the company. Using your knowledge of the client’s exceeded revenue for your own personal profit by buying shares in anticipation of the stock price going up before the next quarterly report is released constitutes insider trading and is deemed illegal.

The Year 1792

Ironically, insider trading was considered an essential competitive advantage centuries ago. History points to William Duer as the first person to make an insider trader transaction. Duer, a former assistant treasury secretary, was largely responsible for the economic crash of 1792. Duer used his government connections to speculate on the debt of the newly created American government.

When Alexander Hamilton became the first secretary of the treasury, he argued that the government should issue bonds to help attract foreign investments and help pay down the government’s increasing debt. Duer used his inside information to learn how these government bonds would be priced before they were released. After some initial success, he began attracting the attention of other investors. He was only too happy to take their money in hopes of increasing his own profits. With this borrowed money, he attempted to corner the market on the newly issued 6% bonds. This collective of investors became known as the “6 Percent Club.” Duer was so sure of his own success that he liquidated most of his assets, including his family estate in New Jersey and defrauded funds from a public lottery where he served as trustee.

Alexander Hamilton was furious at Duer’s behavior and wrote on March 2, 1792: “'Tis time, there must be a line of separation between honest men and knaves, between respectable stockholders and dealers in the funds, and mere unprincipled gamblers." He convinced the Bank of the United States to curtail lending, especially to the “knaves and gamblers”. Hamilton’s efforts caused Duer’s plan to go belly up. Duer was left penniless and unable to pay back his debts, causing him to be chased through the streets of New York by a mob of people trying to lynch him. Eventually, he got reprieve while in debtor’s prison, where he died a few years later. Duer’s double-dealing increased controls on the trading of securities and was responsible for the establishment of the Buttonwood Group, the predecessor of the New York Stock Exchange.

The Year of 1892

Another legendary insider trader was railroad baron Jay Gould. During the Civil War, Gould started a brokerage firm and made a fortune because of his network. In 1869, Gould used his connections to President Ulysses S. Grant in an attempt to corner the market on gold. What Gould really wanted was the price of wheat to rise. He figured if wheat prices increased, farmers would sell more, and this would lead to large shipments of wheat products along one of his railroad lines. Gould speculated that pushing the price of gold up would also increase the price of wheat.

To perpetrate his scheme, Gould tried to convince those close to President Grant that the government should hold off on selling gold. At the same time, Gould’s firm was buying up gold like crazy and refusing to sell it. This scheme caused the Black Friday panic of 1869. The government tried to counter Gould’s deception by flooding the market with $4 million in gold, but Gould and other investors wouldn’t sell. This combination of a flooded gold market and investor hoarding caused the price of gold to plummet, and a panic ensued. A New York Times article published after Gould’s death said in 1892 that his “private sources of information in the field helped him turn almost any success or defeat of the Union army into a profitable account.”

The Year 1909

The first real attempts to curtail insider trading came in 1909. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Strong v. Repide that a director of the Philippine Sugar Estates Development Company committed fraud when he bought stock in his company without sharing pertinent information with the seller that would increase the share’s value. But it wasn't until the stock market crash of 1929 that the Securities and Exchange Commission was created to improve market oversight and enforcement.

The Year of 1980

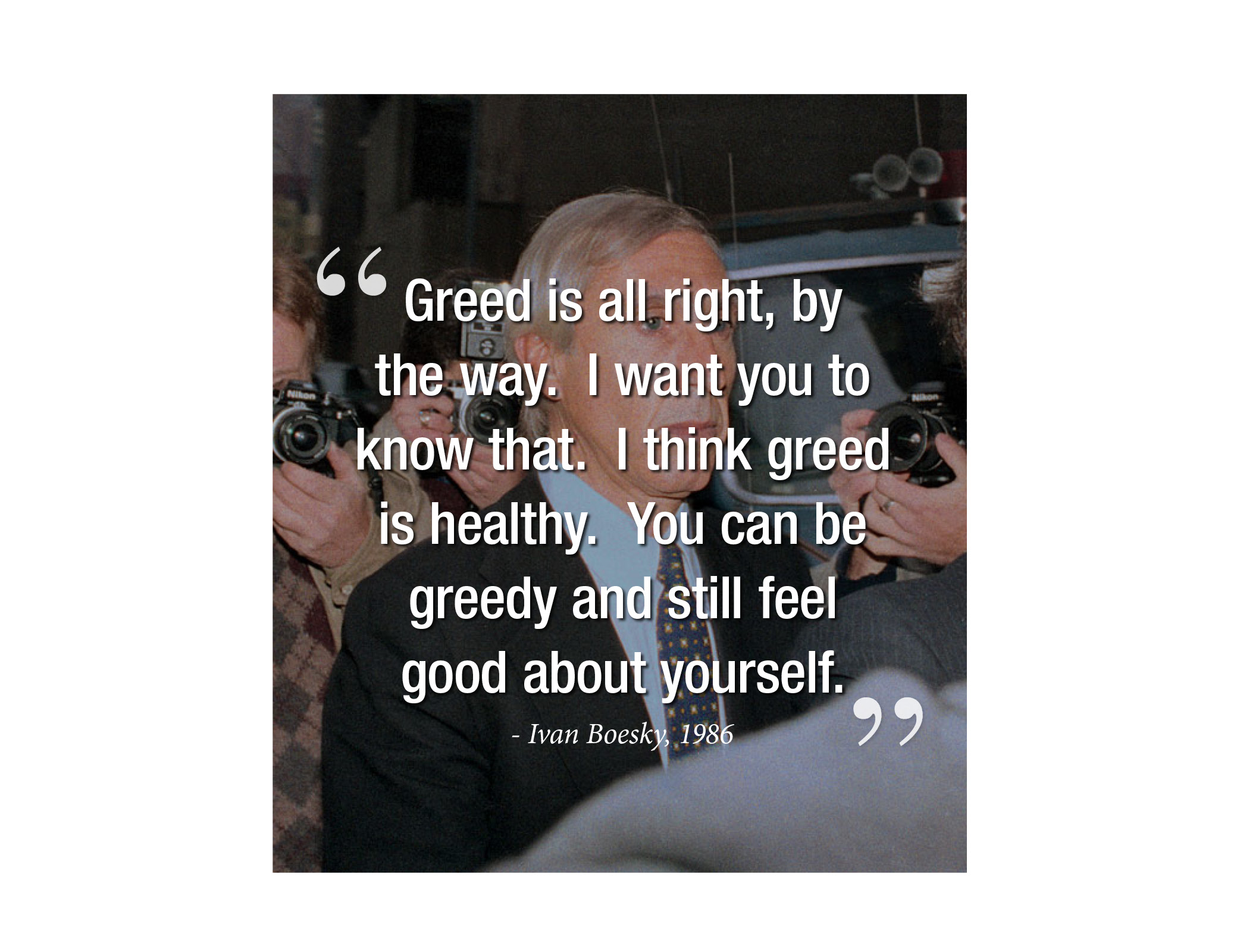

Fast forward several decades, and the market is still dealing with insider trading issues. Ivan Boesky was a Wall Street player who rose to prominence in the 1980s, amassing a fortune in excess of $200 million. He was renowned for betting on corporate takeovers with a practice known as risk arbitrage. Boesky was so successful that he wrote a book, Merger Mania: Arbitrage: Wall Street's Best Kept Money-Making Secret, and gave a famous commencement address at the Haas School of Business Administration at the University of California at Berkley in the spring of 1986. In his speech, he proclaimed "Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself." This speech was adapted for Michael Douglas’s famous “Greed is Good” speech from Oliver Stone’s movie, Wall Street.

Yet Boesky’s success did not stem from quasi-mystical powers that allowed him to predict the future. What he had was material nonpublic information, and he knew the outcome of every corporate merger gamble he took before he placed his bet. It turns out that Boesky was receiving inside information from a key insider at Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc., which was one of the biggest investment banks on Wall Street at the time. His accomplice, Dennis Levine, worked in the mergers and acquisitions department at Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc. and had access to significant amounts of nonpublic information.

Boesky had enticed Levine with an upfront payment of $2.4 million, and Levine dutifully passed along any information he could to Boesky. With this advanced warning, Boesky would purchase as many shares of the targeted companies as he could. Boesky was so brazen that he would often do this only days before the mergers were announced and then sell the shares days later for profits in the millions. But Boesky’s hubris and failure to cover his tracks by purposely betting wrong to diffuse suspicion eventually lead to the SEC taking a keen interest in Boesky’s trades.

The SEC eventually caught up with Levine as the inside source, and he quickly gave up Boesky’s name. Boesky negotiated an arrangement with the SEC and helped them entrap other insider traders, including the high-profile Michael Milken. Boesky was sentenced to three years in prison and fined $100 million. The investigation pulled the rug on a corrupt culture of insider trading on Wall Street during the bull market of the 1980s and lead to the forced bankruptcy of Drexel Burnham Lambert.

The Year 2012

As recent as 2012, the actions of Scott London risked the reputation of an entire profession. Mr. London was a senior audit partner at accounting firm KPMG, LLP in the firm’s Los Angeles office. Through his employment, he had access to the detailed financial records of KPMG clients. This kind of information is clearly material nonpublic information, and London was required by his fiduciary duty to keep that information private. But a combination of compassion, greed and a lack of ethics corrupted London and prompted him to share his inside information with his golfing buddy, Bryan Shaw.

Shaw was a part owner of Shaw Diamond Company of Encino, California and had befriended Scott London at their shared country club, the North Ranch Country Club. The two soon became regular golfing partners and fast friends. After the 2008 economic crash, Shaw’s family business was in dire straits, and London decided to help his friend out with stock tips involving KPMG clients. Specifically, London passed along earnings information about Herbalife, Sketchers and Deckers to Shaw and also gave him early information on potential mergers involving RSC Holdings and Pacific Capital. According to the SEC complaint, Shaw netted $1 million from the illicit trades. Shaw and London would often meet near Shaw’s diamond store and make covert exchanges of thousands of dollars in manila envelopes wrapped in black paper bags. Mr. Shaw even gave his good friend a Rolex watch for his troubles.

In a recorded telephone conversation, London offered the following advice to Shaw to avoid detection: “What you do is you start just buying in small blocks, right, so it doesn’t draw attention and then, you know, then it doesn’t look unusual at all.” Despite London’s warning to Shaw, Shaw had other plans on how he would use the trading information. When London tipped Shaw in advance of Union Bank’s takeover of Pacific Capital in February 2012, Shaw went on a buying bonanza of Pacific Capital stock and call options. When the deal was announced, Pacific Capital share price rose 57% and Shaw profited $365,000. This transaction proved to be “the straw that broke the camel’s back”. Mr. Shaw’s bank froze his account and alerted the SEC to the potential of insider trading. Shaw immediately contacted London and London told Shaw not to worry and that “insider trading was like counting cards at a casino in Las Vegas; if you were caught, they simply ask you to leave because they cannot prove it.” But the SEC and FBI were biding their time, building their case and waiting for a slip up.

That slip up came in January of 2013 when London was working on an audit for Herbalife. He noticed that the Herbalife’s actual earnings were better than what was being estimated by Wall Street. London thought this would be a good opportunity for Shaw to buy some Herbalife stock, since typically better than expected earnings reports usually leads to a bump in a company’s stock price. London passed the information to Shaw, and Shaw purchased the shares.

The FBI made their move and approached Shaw first. He quickly agreed to cooperate and helped them continue to gather evidence against London. He continued to play along with the Herbalife deal, but this time he was recording his clandestine telephone conversations. When the time came for the exchange, the FBI followed along and recorded the entire conversation. The jig was up and a few weeks later, on March 20th, the FBI paid Scott London a visit at his picture-perfect house, on the picture-perfect cul-de-sac,with his picture-perfect neighbors looking on in shock. Mr. London had no choice but to admit to everything and come clean. He maintained that Bryan Shaw was the only person he gave information to and through his lawyer issued a lengthy statement in an attempt to save KPMG’s reputation. “I regret my action in leaking non-public data to a third party regarding the clients I served for KPMG. Most importantly, and I cannot emphasize this enough, is that KPMG had nothing to do with what I did.” KPMG was forced to resign as auditor of Skechers and Herbalife.

As shown in this chapter, insider trading has plagued the financial markets for centuries; it is no surprise that Garrett, Ken and Matthew were attracted to the concept. But as we’ll see later on in this e-case, all good schemes must come to an end.

When Garrett was working at Weiss, Peck & Greer, he met Ken Robinson. Ken had worked in residential real estate in New York but was now with Garrett at Weiss, Peck & Green. Garrett and Ken became fast friends. Soon one of Ken’s friends, Matthew Kluger, joined the group, and an insider trader trio was born.

After attending and graduating law school, Matthew landed a job at Cravath Swaine & Moore in 1995. Cravath Swaine & Moore was one of the world’s most prestigious law firms, and their client list included some of America’s top corporations. He was assigned to work in the mergers and acquisitions practice area, and that’s when the plan was born.

Matthew, through his position and work associates, was privy to sensitive information on potential corporate mergers and takeovers. After doing some thinking, he decided to reconnect with Ken. According to published reports, the two met for lunch and after telling Ken about his unique situation, Ken had an idea.

According to published reports, Matthew was sold on Ken’s idea, but Matthew knew they needed a third party unconnected to him to make it work. Matthew couldn’t just buy stocks himself based on his information. If Ken purchased the stocks, eventually the SEC would find the connection between Matthew’s position at the law firm and Ken’s timely and profitable stock purchases; that’s where Garrett came in.

With Ken’s help, Matthew would be completely unconnected to the person buying the stocks that he tipped with his inside information. Ken just had to convince Garrett, who had recently become a full-time stock trader. He met Garrett for a few drinks and began his sales pitch.

Caption: Garrett discusses his friendship with Ken

After a few years, each member of the group had made a few hundred thousand dollars. In 1999, Matthew moved to a new firm, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, and just like that, the insider trading was over. Unbeknownst to Ken and Garrett, Matthew left the firm after being questioned by the SEC. The SEC was questioning Mathew’s involvement in divulging sensitive information from his firm. Matthew denied any wrongdoing and provided the SEC with his banking and phone records. The investigation didn’t lead anywhere, but it was enough to scare Matthew straight.

Caption: Garrett talks about the large amounts of money he made through his trades

Garrett had used his misbegotten profits to kick-start his burgeoning trading career and eventually landed a plum position at RBC Professional Trading Group. Ironically, he figured out how to stay profitable most of the time, so he didn’t really need Matt’s inside tips anymore. Garrett was a hard worker and soon realized profits in the millions; profits based on legal trades.

Although Garrett was experiencing success, the life of a trader is one of ups and downs. He was making big money now, but he was also losing big money too; and greed and the lure of the quick buck have a funny way of making people do things they shouldn’t.

Caption: Garrett talks about e-trading

For Ken, life had changed significantly. He had gotten married, started a family and was living in suburban Long Island when, one day, he got a phone call from Matthew. Ken actually needed the extra money now, so the call from his old insider trading buddy was welcomed. Matthew had recently been hired by a Virginia-based law firm, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, working in mergers and acquisitions. The insider information was about to start flowing again; they just had to get Garrett back on board.

Ken appealed to Garrett’s sense of friendship, mentioning he really needed the money to support his growing family. Although hesitant at first, Garrett eventually agreed to rejoin the team out of a sense of loyalty to his close friend. The trio was back together and got ready to trade.

After Matthew’s scare with the SEC a few years prior, he went about gathering information much more covertly this time. He browsed his law firm’s document management system, looking for documents related to pending mergers or acquisitions. He was careful not to open any of the documents and to look only at the titles and subject lines. It was a more tedious process, but he knew if he opened any documents, it would create a record which could get back to the SEC. Another new precaution for the trio this time around was using disposable cell phones for their clandestine conversations.

Caption: Garrett talks about the trio’s new use of cell phones in their scheme

Garrett’s Little Secret

The Bauer-Robinson-Kluger team was committed to the scheme and agreed to keep the operation small so as to not arouse suspicion. However, Garrett had developed a “go big or go home” mentality. Unbeknownst to Ken and Matthew, he was trading in bigger and bigger numbers. Garrett would often purchase stocks for Ken and Matthew in the range of 20,000 to 30,000 shares; but if the deal seemed good, he would often double and triple the purchase in the hundreds of thousands and even millions. One such deal was Oracle’s acquisition of Sun Microsystems in 2009. Bauer was able to net almost $11.4 million in profits from Matthew’s tip with the vast majority of the money going into his own pockets.

In total, Garrett traded on at least nine pending deals involving companies on Wilson Sonsini’s client list and brought in a profit of nearly $33 million. Only $350,000 went to his two partners, according to court documents. Thirty-three million dollars is hardly chump change; it was no surprise that Garrett attracted the attention of the SEC.

Garrett received information requests from the SEC about some of his trades and was requested to hand over banking and phone records. When nothing suspicious was detected by the SEC, Garrett felt like the plan had worked. Although Garrett and Ken were best friends and spoke almost on a daily basis, the SEC hadn’t yet connected the dots between Garrett, Ken and Matthew.

The SEC scare was enough for Garrett to get out of the insider trading racket, and he broke the news to Ken that he was ending his role in the scheme. Garrett warned Ken to no longer trade on any of the information from Matthew. Garrett believed that the direct connection between the two of them would surely be noticed by the SEC, and it was just too risky. Ken promised, “No more trades.”

Caption: An expert weighs in a Garrett’s scheme

In the fall of 2009, Matthew came across very specific nonpublic information about Hewlett-Packard acquiring 3Com Corporation. It turned out that Ken already owned 3Com stock, so he figured that buying more of a stock that he already owned wouldn’t arouse suspicion. Matthew’s tip seemed ironclad, and he needed the extra money, so he went ahead and bought more stock. With that, Ken made a profit of $200, 000 to share with Matthew. However, the exchanged didn’t go unnoticed by the SEC, as Ken had hoped.

Almost a year later, when Ken made $500, 000 on Matthew’s tip that Intel was buying McAfee, the SEC knew something was suspicious about the transactions. The SEC revisited the records they got from Garrett. They were quickly able to link Ken to Garrett, and they soon discovered Ken’s friendship with Matthew. Next, they went back and looked at their records from Matthew’s initial encounter with them a few years prior and were confident they could see a clear pattern of communication among the trio. Now, the SEC just needed proof, so they waited and watched, knowing the power of greed would compel the group to try again.

In January of 2011, Garrett lost over $4 million from his involvement with Lighthouse Financial Group, a small trading firm that had just filed for bankruptcy. When he received a call from Ken about a tip relating to the merger of Zoron Corporation and CSR PLC, the sting from the $4 million loss helped him agree to the scheme against his better judgment; he decided to trade on the nonpublic information. Garrett was able to make $2 million on this trade and kept most of it for himself. Only $175, 000 went to Ken and Matthew to share. This would prove to be the group’s final trade.

On March 8, the FBI visited Ken’s home, and the jig was up. Ken had no choice but to cooperate and admitted everything, but the FBI wanted more. The FBI wanted Ken to help them incriminate Matthew and his best friend, Garrett, and asked him to record phone conversations with the two men. A few phone calls later, and the FBI had all the evidence they needed.

The government determined that Garrett Bauer, Ken Robinson and Matthew Kluger illegally traded on over 30 corporate transactions over a 17-year span. The illegal trades generated $37 million in illicit profits with the bulk of the profits (approximately $33 million) going to Garrett. Although Garrett profited the most from the scheme, it was Matthew Kluger who bore the brunt of the responsibility and culpability, as he was the one who betrayed the trust of his employers and leaked sensitive material nonpublic information.

Caption: Garrett talks about his experience in prison

During sentencing, U.S. District Judge Katharine Hayden claimed that Matthew behaved in an “amoral nature, where anything and everything involving trust and honor was thrown out of the window because of that blissful access to information that Mr. Kluger enjoyed.” She also claimed that his actions were particularly insidious because as a lawyer, he had taken oaths of integrity and honesty. She finished by saying that: “People stay out of the market in part because they think it’s skewed toward the insiders. These people may be right.”

Caption: An expert talks about the rationale behind Garrett’s sentencing

Garrett Bauer was sentenced to nine years in prison. Matthew Kluger was sentenced to 12 years, which ranks as the longest prison sentence for insider trading in U.S. history to date. Ken Robinson, who cooperated with authorities and helped to further incriminate both Garrett and Matthew, was sentenced to 27 months in jail.

Caption: An expert talks about what tipped the SEC to Garrett’s insider trading

In an attempt to make sense of what he did and to help others avoid the temptations that conquered him, Garrett lectured about his experiences at nearly 150 events, mostly to university students across the country, prior to his sentencing.

NYU adjunct professor Mark Brennan described what his students witnessed from Garrett’s case:

“Someone, different from them only in age, ruined his life through a combination of greed, deceit, and carelessness. No ‘Scared Straight’ program could hope to be as effective as the one Garrett provided.”