Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes: How Following Orders Can be the Wrong Choice

| Site: | Helios Digital Learning |

| Course: | Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes: How Following Orders Can be the Wrong Choice (Crane) |

| Book: | Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes: How Following Orders Can be the Wrong Choice |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, March 13, 2026, 1:23 PM |

The story matters.©

© 2013 Helios Digital Learning. All rights reserved.

This e-case may not be duplicated, altered or distributed in any way without the express written consent of Helios Digital Learning, Inc.

Summary: Exercising professional skepticism is one of the most important responsibilities of an auditor and an accountant. According to AU 230.09, a skeptical auditor is one who “neither assumes that management is dishonest nor assumes unquestioned honesty.” This standard is heavily cited in the authoritative auditing literature; however, these can be difficult assumptions to maintain. This case highlights one accountant’s struggle with exercising professional skepticism while evaluating a client’s financial statements. Additionally, this case discusses how exercising professional skepticism can be important in identifying fraud.

Learning Objectives: After reading the case students will:

- Gain an understanding of the importance of professional skepticism.

- Gain an understanding of audit quality.

- Improve critical thinking skills.

- Gain an understanding of the role accountants/auditors have in fighting fraud.

Harold Katz is a former executive of Lancelot Investment Management, the now defunct Chicago-based hedge fund founded by Gregory Bell. Before joining Lancelot, Harold had a successful career working as a certified public accountant (CPA) at some of the country’s most prestigious public accounting firms and privately held corporations. Harold described himself as a team player willing to offer assistance whenever and wherever he was needed. He was a reliable and loyal employee. But that loyalty eventually led Harold to be compliant in one of the largest Ponzi schemes in U.S. history. His refusal to act turned this mild-mannered accountant into a white-collar felon.

Caption: Harold Katz discusses his background.

Hedge funds were Harold’s specialty. Working in the hedge fund environment can be quite unique in comparison to public accounting. Historically, hedge funds are thought to be a highly secretive, very lucrative form of employment where personality fit is key to survival. Harold always considered himself to be an individual who followed authority and attributes these characteristics to his South African upbringing.

Prior to the troubles Harold experienced at Lancelot, he thoroughly enjoyed his job and welcomed the change from the public accounting culture. He enjoyed hedge fund work, the people and, most importantly, he respected and trusted his CEO, Gregory Bell.

According to the SEC complaint, Lancelot Investment Management, LLC was a Delaware Limited Liability Company with offices in Northbrook, Illinois and was organized by Bell in 2001. Lancelot managed three hedge funds that were organized as limited partnerships. These hedge funds were Lancelot Investors Fund, LP (“Lancelot I”), Lancelot Investors Fund II, LP (“Lancelot II”) and Lancelot Investors Fund, Ltd. (“Lancelot Limited”) also known collectively, as the “Lancelot Funds.”

Bell served as the General Partner of Lancelot I and Lancelot II and as investment manager of the Lancelot Funds. Ultimately, all funds were managed by Bell, who owned 99% of the holding company that owned Lancelot Management.

Before Lancelot Management, Harold worked for two accounting firms which had performed the yearly Lancelot financial statements audits from 2003 to 2007. Harold was the senior manager/director of these audits during this time period.

Harold was hired by Lancelot in 2007 to serve as Vice President of Finance and Accounting. He was paid an annual salary of approximately $150,000 and was to receive a one-time bonus of $10,000. He worked at Lancelot for 15 months before the company imploded.

There has been significant discussion and concern regarding audit quality when an affiliation exists between the external auditor and the client. Audit quality is defined as the joint probability that an existing problem is discovered and reported by the auditor (DeAngelo, 1981). If a problem exists, the probability of problem discovery depends on the auditor’s competence and effort and on the ability of senior executives to hide or minimize the problem’s appearance. The probability that an auditor reports a discovered problem largely depends on auditor independence. The concern is that collusion—either explicit or implicit—can occur between the auditor. The appearance of impropriety increases when an auditor begins working for the client he or she once audited. In such a situation, the former auditor may be less likely to confront management with problems uncovered during the audit.

Audit quality research identifies three types of affiliations that can jeopardize auditor independence: employment affiliation, alma mater affiliation and chance affiliation. As in Harold’s case, employment affiliation happens when an individual leaves the audit firm to work for a client. Alma mater affiliation happens when an executive convinces his company to appoint his former audit firm. Chance affiliation happens more randomly. For example, an individual may have trained at a particular audit firm and, years later, the employee’s new firm may hire his previous employer.

All of these affiliations can have an impact on audit quality and auditor independence. For example, the auditor may be too friendly with the client depending on the prior affiliations or the auditor may be too familiar with the auditor’s testing methodologies which could make it easier to circumvent those controls.

In Harold’s case, employment affiliation with his previous audit firm and Lancelot may have affected Harold’s level of professional skepticism. For example, the Lincoln Savings & Loan vs. Wall case (1990) revealed that Charles Keating offered an annual salary of $930,000 to hire an audit partner who had worked on the Lincoln engagement. The court ruled that auditor independence can be impaired when an auditor accepts an offer of employment from a client.

Over 20 years ago, Deloitte & Touche agreed to pay a $65 million penalty following its audit of Bonneville Pacific due to the fact that several Bonneville executives had previously worked for Deloitte & Touche, and the plaintiffs claimed this impaired the audit firm’s independence (Clikeman, 1996).

Additionally, financial press reports suggest executive-auditor affiliations prevented auditors from discovering fraud in the case of Livent, a Canadian producer of Broadway shows (Beasley et al., 2000). Senior management were former employees or partners of their companies’ audit firms in the audit failures of Cendant, First Executive, Phar-Mor, and Waste Management (Clikeman, 1996; Buckless et al., 2000; Business Week, 2002). It is important to note that all of these cited cases occurred pre-Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act. Post SOX, executives holding accounting or finance positions CANNOT be employed by their company’s audit firm during the year following their participation in the external audit.

These affiliations can be problematic for the organization, but also problematic from the employee’s perspective. Since Harold was once responsible for the Lancelot audits when he worked for their external auditor, it made it difficult for him to claim that he had no knowledge of the fraud. Even if he honestly did not know about the fraud, his previous affiliations with Lancelot run counter to his claim of ignorance.

Caption 2: Harold explains how his story is different from typical white-collar cases.

Caption: Harold explains the effects his imprisonment had on his life.

Tom Petters and Greg Bell met when Bell was managing director of a Florida hedge fund that purchased promissory notes from Petters’s company. During the mid-1990s, Petters began raising funds for his businesses by selling Petters Company Inc. (PCI) promissory notes. Investors included individuals, retirement plans, individual retirement accounts, trusts, corporations, partnerships, and other hedge funds. Petters urged Bell to leave the Florida hedge fund and start his own hedge fund, which led to Bell eventually starting Lancelot Investment Management. Lancelot Investment Management (and Bell) raised $2.62 billion from hundreds of investors through the sale of interest in Lancelot’s three hedge funds. The majority of the funds raised were invested into promissory notes from one firm, Petters Company Inc. Lancelot was actually one of three feeder funds that heavily invested the majority of their funds into Petters Company Inc.

Caption: Dean Lewis describes Tom Petters.

Investors in both Petters Company Inc. and Lancelot Investment Management believed that they were purchasing promissory notes to finance the purchase of vast amounts of consumer electronics by vendors who then resold the merchandise to "big-box" retailers, including well-known chains, such as Wal-Mart and Costco. Per the SEC complaint, investors also believed:

- The promissory notes were secured by underlying merchandise inventory.

- Purchase order inventory financing consisted of transactions in which Petters Co. arranged for the sale and delivery of end-runs or overstock merchandise.

- These transactions usually took up to 180 days to complete and that the manufacturers demanded payment up front while the retailers did not pay until the merchandise was delivered.

- Petters Co. needed the investors' money to finance these transactions for the 180-day periods between the retailers' orders of merchandise and the retailers' payments for the goods.

- Investors would receive high rates of return on the Petters Co. notes, typically at least 11% per year.

All of these “promises” were outlined in the investor memorandum that was issued and used to entice potential investors.

It’s important to remember that Harold was intimately acquainted with Lancelot’s finances, as he was the auditor to Lancelot between 2003 and 2007. After deciding to take the offer to work for Lancelot in 2007, Harold noticed that payments on some of the Petters Company Inc. promissory notes were late. This problem persisted in 2008.

According to the SEC complaint, instead of reporting the delinquent promissory notes to investors, Bell and Petters agreed to extend Petters’s payment of the PCI promissory notes from 180 days to 270 days. Harold was aware of this arrangement. The fact that the promissory notes were delinquent was material and was only disclosed to a few investors that pressed the issue with Petters.

Unfortunately, the 90-day extension did not help, and the promissory notes remained delinquent after the extension ran out. Again, Harold was aware of the delinquency and did not disclose this information to any investors. Following the direction of his boss, Harold assisted in developing a plan that would present a false representation to investors.

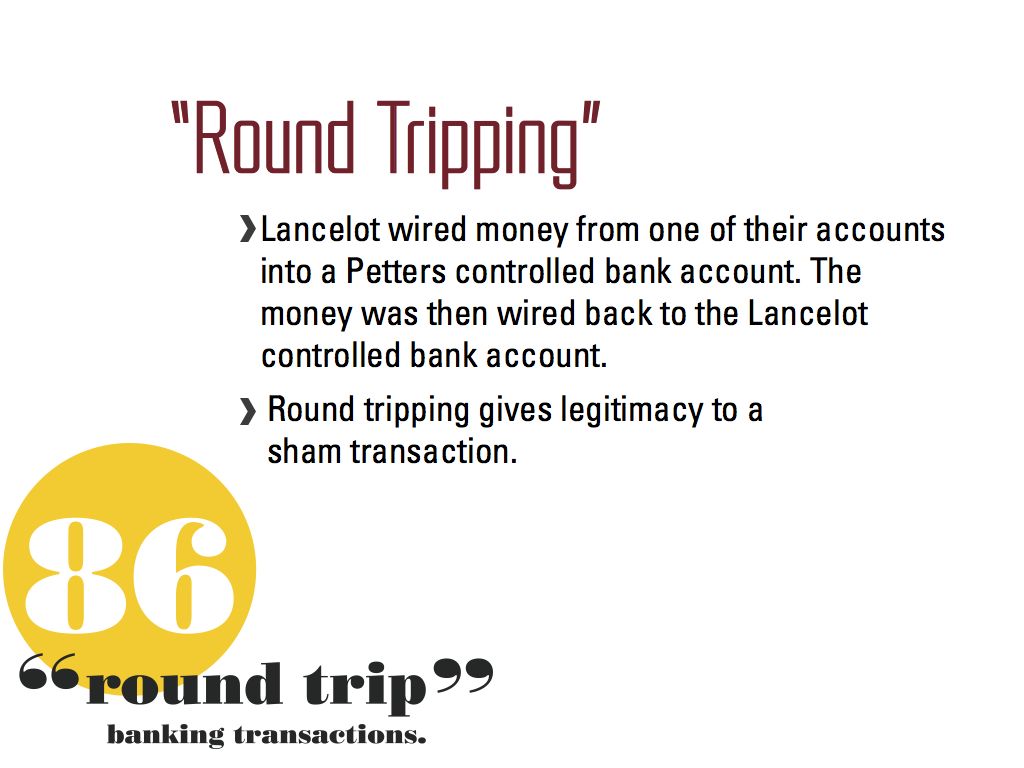

According to Harold’s plea agreement, he conspired with Bell and individuals at Petters Company to make approximately 86 fraudulent “round trip” banking transactions that gave investors and potential investors the false impression that Petters was paying its promissory notes.

These round trip transactions consisted of Lancelot wiring money from one of their accounts into a Petters Company controlled bank account. Then, the money was wired back to the Lancelot controlled bank account. The transactions were designed to make it seem as though Petters Company was paying on the Lancelot promissory notes. In essence, Lancelot was giving Petters cash, and Petters was using the Lancelot cash to pay Lancelot. Round tripping gives the appearance of a legitimate transaction when, in fact, the transaction is a sham.

Round tripping is a common fraud scheme used to inflate earnings, and even large-scale public companies have been accused of engaging in this scheme. Years ago, Time Warner (formerly AOL) agreed to pay a $300 million fine due to round tripping transactions. Time Warner was “effectively funding its own online advertising revenue by giving the counterparties the means to pay for advertising that they would not otherwise have purchased.”

Caption: Dean Lewis describes feeder funds.

When investors asked for details regarding the pay-off status of the promissory notes, Harold prepared a spreadsheet showing the Petters Co. promissory notes had been “paid” or “partially paid.” Harold did this at the behest of his boss, Greg Bell. Yet, these notes were “paid” only by the round tripping transactions. These false representations were used to solicit $243 million from new investors.

Caption: Harold explains the reaction to the Petters fraud case.

Although Petters and the feeder funds, including Lancelot, made significant promises in order to attract investors, the entire operation was a scam. Harold had no direct contact with Petters, however, he did participate in the fraud by misleading Lancelot investors and other potential investors. The Petters fraud was discovered when Deanna Coleman, a longtime Petters employee, informed law enforcement that she had engaged in a multi-billion dollar Ponzi scheme with Petters for over ten years. She agreed to wear a wire in order to implicate Petters and other co-conspirators in the massive fraud. According to the civil complaint it was revealed that:

- There were no retailers, "big-box" or otherwise.

- No one ordered any merchandise through Petters Co.

- All of the underlying documentation (purchase orders, bills of sale and assignments of security interests) had been fabricated by Petters and others acting at his direction.

- The two vendors Petters claimed he worked with were shell companies with no real operations and the principals were associates of Petters.

- Each vendor had opened a bank account at the request of Petters. The vendors deposited monies wired to them from investors of Petters Co., took a percentage of that money as compensation for their role in the scheme and returned the rest to Petters.

Caption: Dean Lewis explains the ripple effect of the Petters fraud.

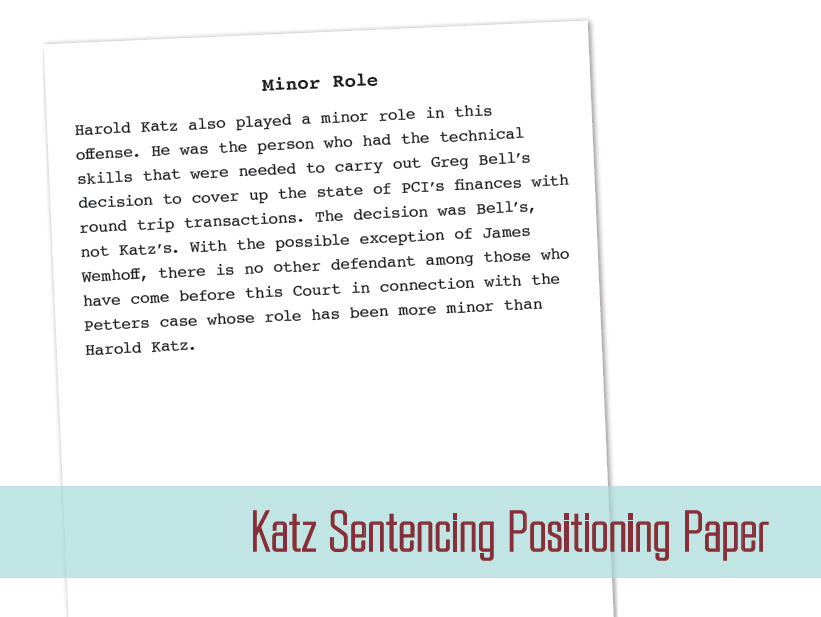

Harold Katz pled guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and was sentenced to 366 days in federal prison. Harold participated in the country’s third largest Ponzi scheme to date and the largest Ponzi scheme in Minnesota history. It is questionable whether Harold exercised an adequate level of professional skepticism when dealing with the Lancelot audit, the Petters Company transactions and his CEO, Greg Bell.

Caption: Dean Lewis explains how the money from the fraud scheme was recovered.

Caption: Harold describes the lack of due diligence in the Petters case.

According to published research on major U.S. Ponzi schemes between 2002 and 2011:

- The most common Ponzi scheme involved fraudulent hedge fund investments.

- Other common schemes included real estate investment frauds, fraudulent promissory notes and fraudulent foreign exchange trading programs, respectively.

- Nearly 40% of Ponzi schemes are conspiracies perpetrated by multiple individuals.

- Nearly 1 in 4 Ponzi schemes involve the use of affinity group targets to build the fraud and increase the scheme’s “credibility.”

Although Harold was following his boss’s orders, he was still implicated in the fraud.

Following the boss’s orders is not a defense that can stand up in a court of law. Betty Vinson, former CPA and Worldcom accountant, found herself in a situation similar to Harold’s. At the direction of Worldcom senior management, Vinson and other WorldCom employees improperly capitalized line costs to overstate pre-tax earnings by approximately $3.8 billion. According to the SEC complaint:

“Vinson knew, or was reckless in not knowing, that these entries were made without supporting documentation, were not in conformity with GAAP, were not disclosed to the investing public, and were designed to allow WorldCom to appear to meet Wall Street analysts' quarterly earnings estimates.”

Betty was sentenced to five months in prison and five months home detention for her role in WorldCom's accounting scandal. She was also sentenced to three years on probation.

Despite the fact that Harold played a minor role in the Petters fraud, he still was sentenced to 366 days in federal prison. According to the Harold’s plea agreement:

Those notes had borne 180 day maturities, but the defendant learned that they would now have 270 day maturities.

Because the defendant is a professional accountant, he must have realized that this extension meant there were problems with the performance of PCI.

The defendant also knew that Lancelot’s investment portfolio was almost entirely made up of PCI promissory notes, and could therefore have drawn the obvious conclusion about what problems with PCI’s financial performance would mean for Lancelot.

“Harold Katz also played a minor role in this offense. He was the person who had the technical financial skills that were needed to carry out Greg Bell’s decision to cover up the state of PCI’s finances with round trip transactions.”

Caption: Harold explains what he learned from the situation.

Caption: Harold explains the mindset of the typical accountant.

From Harold’s plea agreement:

“Upon being notified that he was a target of the federal investigation, Katz retained counsel, and through counsel, immediately began cooperating with the authorities. He answered all the questions that law enforcement agents and prosecutors asked him. He acknowledged his own conduct. He testified before the grand jury and described to the grand jury the operations of Lancelot and the round trip transactions. Katz walked the grand jury through a packet of documents that illustrated a specific round trip transaction.

The Court should also, however, factor in to its sentencing decision the gravity of Katz’s conduct. He is a CPA, a person who by virtue of the role his profession plays in the business and financial system is expected by society to guard against fraud, and is not a person who should become complicit in fraud himself. Katz had not only been an audit accountant - the sine qua non of the accounting profession’s function as protector of financial integrity - he had audited Lancelot itself, more than once.”

Caption: Harold discusses his plea agreement.

Caption: Harold describes the people he encountered in prison.

So how did this loyal, compliant, mild-mannered CPA handle his federal prison time at Fort Dix?

Caption: Harold describes his time at Fort Dix.

Where is Harold Now?

Harold is currently working and trying to rebuild his life after the Petters fraud. A felony conviction, even a short sentence, can have a lifelong impact, professionally and personally.

- Define professional skepticism, and discuss why this is important to the accounting profession.

- Define the three types of audit affiliations? Which type(s) were present in Harold’s case?

- Discuss Harold’s role in the Tom Petters Ponzi scheme?

- Based on your understanding of Harold’s plea agreement, why was he sentenced to 366 days in federal prison?

- In your opinion, should Harold have followed his boss’s orders? If you were placed in a similar situation, how do you think you would respond?